The Cambridge Capital Controversies: a Keynesian overview

Going to (hopefully) Re-switch back to posting consistently

The rationale for most neoclassical economic theory is taught as rather intuitive, and in (probably) most undergraduate institutions, it is not challenged. The purpose of this post is to share my notes on what led me, an undergraduate student, to challenge my thinking on neoclassical capital theory. This post examines the implications of the Cambridge Capital Controversies from a post-Keynesian perspective.

Background

The general background to the Cambridge Capital Controversies was the Harrod-Domar model, one of the first attempts to develop a theory of economic growth. The Harrod-Domar model is not particularly important for this post; what is more important is the Solow model, which addressed some strange results in the Harrod-Domar model, such as unstable unemployment rates and instability in different types of growth rates, e.g., potential (natural) and actual. Furthermore, the Harrod model exhibited explosive or collapsing growth rates when its parameters did not match in specific ways. The Solow model appealed to marginalism through a well-behaved Cobb-Douglas production function that upholds the theory of marginal productivity. Further assumptions in the Solow growth model include an exogenous natural growth rate (the maximum growth rate, equal to the sum of labor force growth and productivity growth). The Cambridge Capital Controversies were named for the debate, which was primarily between economists such as Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa from Cambridge, UK, whilst the neoclassical view was advanced from Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Robinson and Capital

The Cambridge Capital Controversies showed that well-behaved aggregate production functions, such as the Cobb-Douglas, rely on circular reasoning. Joan Robinson is primarily credited with being the first to speak loudly in her critique of the Cobb-Douglas production function. To demonstrate this, take the standard Cobb-Douglas production function (CDPF):

The marginal product of capital (MPK) is defined as:

The MPK and marginal product of labor are supposed to be equivalent to the interest/profit/rental rate of capital and the wage rate of workers:

The issue is that the standard neoclassical response to how to aggregate heterogeneous capital goods is to use a summation of prices of capital goods; however, pricing capital goods in money terms requires knowledge of the interest rate:

Effectively, neoclassicals run into an issue: to value capital, they need the interest rate to, but then to find the MPK/interest rate, they need capital. Instead of CES or Cobb-Douglas, post-Keynesians are likely to use fixed coefficient or Leontief production functions in their models. The idea behind the Leontief production function is that, for a given technology, capital requires fixed labor and capital for a specific output. Consider a cake recipe. If one wants to follow a particular recipe (the output), one must follow fixed inputs, e.g, flour, sugar, etc, to produce said output. In post-Keynesian analysis, most production follows these lines. This essentially means that, as long as there is no bottleneck (spare capacity) on inputs, the fixed-coefficient type marginal cost curves won’t rise in the post-Keynesian worldview. The standard Leontief production function is given below:

Since the post-Keynesian view of the use of production functions has been presented, the real meat and potatoes of the debate shall be given. This deals with the issues surrounding the choice of technique and Wicksell effects.

Sraffa & Commodities

Before I start this section, I want to give a big shout-out to my friend Henry, who inspired me to learn economics and decide to major in it. I am grateful, especially for this post, as Henry gave me some notes that heavily influenced this section on mathematics for re-switching and, more broadly, capital theory.

Piero Sraffa’s work ‘The Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities,” was a work of art in capital theory and economics broadly. The circularity in capital has already been discussed; this section turns to Sraffa’s revival of classical political economy. Sraffa researched extensively the works of David Ricardo, especially concerning his ‘standard commodity,’ corn. The corn economy assumed diminishing returns to corn inputs through marginalist thinking, and that one could derive the surplus from marginal assumptions. The issue is that no such single-commodity economy existed. Sraffa’s revival of the Surplus approach is that output is determined first, and that distribution and prices come from input-output frameworks.

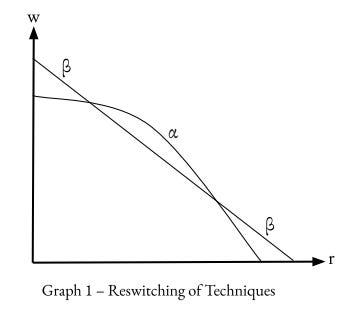

According to Sraffa, capital is not simply a separate input in production; instead, capital is a subset of produced commodities that serve as inputs in future production. In other words, capital is ‘produced means of production.’ Labor, which Sraffa treats as homogeneous in terms of labor hours, helps produce capital through past production chains. Sraffa starts his project with a simple subsistence economy that makes no surplus; he then adds more realism by, for example, considering the distribution of income over the surplus created by production. Sraffa’s system gives birth to a choice of technique that offers a switch point: re-switching. Re-switching involves two methods, each with parameters 𝛼 and ß. The choice of technique assumes that there are fixed (Leontief) coefficients for each method. Now that some core assumptions have been stated, we can justify the model’s mathematical framework. Assume there are two goods, one being a capital good, denoted with subscript k, and the other being a consumer good with subscript c:

Where w is the wage rate, l denotes labor, and p denotes price.

Solving for the wage rate yields, given the prices yields:

As r changes, one would expect a smooth monotonic relationship with a rising capital-to-labor ratio and a lower profit rate. However, under the Sraffian system, there is a non-monotonic relationship between the choice of technique with r and w.

The non-linear relationship between the techniques and the r-w graph also opens the door to the concept of reverse capital deepening. The capital-to-labor ratio is lower at a lower rate of r after the switch point from technique 𝛼 to ß, instead of smoothly increasing with a lower rate of r as neoclassical theory would predict. Some, such as Bohm-Bawerk, assume that capital can be measured independent of prices due to the degree of ‘Roundaboutness.’ Roundaboutness assumes that capital-intensive methods yield greater productivity. Note that Henry should be credited for the mathematical simplicity here as well. Assume that producing a Pepsi takes 7 hours of labor and that it is sold 2 weeks later. Another can of Pepsi is produced in 2 hours, with non-syrup inputs made 3 weeks before sale and syrup made 1 week before sale, requiring 6 hours of labor. As Henry noted, the equations would come out as:

Where the other can is given as:

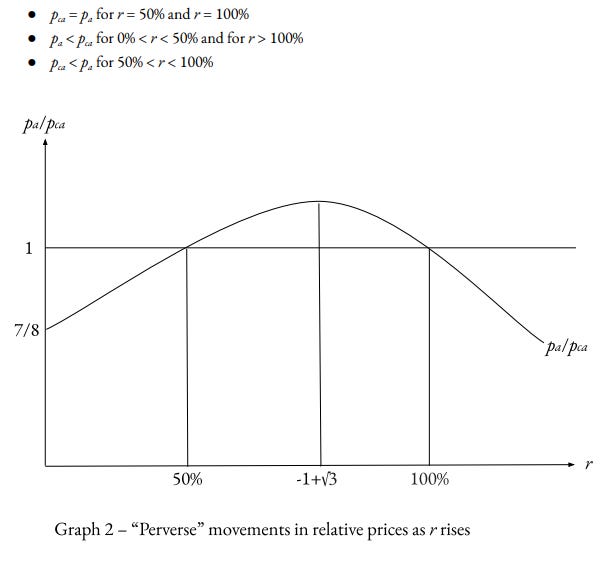

This implies a compound interest of labor employed in the production process: This gives multiple solutions depending on the variable r:

If r is 0, then there all expenses go to wages, however, as r varies, the relationship is non-linear as r grows. Depending on the rate of r, the relative price ratio can change.

The Last Hope for Neoclassicals

Paul Samuelson tried to save neoclassical theory during the Cambridge capital controversy by his surrogate production function. Essentially, he tried to use the Sraffian system under very restrictive assumptions, e.g, controlling for the Wicksell effects that led to some questionable conclusions, as Anwar Shaikh brilliantly says:

In response to Joan Robinson’s challenge, Samuelson (1962) set out to explain how a Sraffa-type book of blueprints could be reconciled with a well-behaved neoclassical production function. Unfortunately, his Surrogate Production Function turned out to depend critically on the assumption that all industries have the same capital labor ratio. Pasinetti (1969) and Garegnani (1970) demonstrated conclusively that the parable of an aggregate production function could not be sustained under more general conditions. Indeed, Garegnani (ibid, p. 421) demonstrated that the only case in which surrogate production function behavior held was with equal capital-labor ratios in each industry. This is a delicious historical irony, because it implies that prices must conform to the simple labor A. Shaikh 12/02/09 Rethinking Microeconomics: A Proposed Reconstruction 12 theory of value (Shaikh, 1973, pp. 11-14, 66-83

Samuelson eventually conceded to the Cambridge, UK crowd on the Sraffian and Robinson issues with neoclassical capital theory, and so the final attempt at a last defense began. Solow, the origin of the Solow-Swan growth model that in many ways was a catalyst for this debate, appealed to the empirical consistency of the data with what the Cobb-Douglas production function would predict. As a university student, Anwar Shaikh examined this issue and found that the Cobb-Douglas function is not empirically verifiable and yields only tautologies about the statistical constancy or variation in the wage and profit shares in national income accounts. In other words, the Cobb-Douglas production function and other well-behaved aggregate production functions are never empirically verifiable; even if they fit statistical results, they merely state tautologies (for more reading, see the links I posted).

Concluding Thoughts

The Cambridge Capital Controversies represent what could have been a breaking point for economic theory; however, as stated in the opening, in most neoclassical institutions, critiques or challenges are rarely mentioned, and when it is mentioned by neoclassical authors, e.g., Piketty in ‘Capital in the Twenty-First Century’, they brush the debate off as worthless and stick to marginal assumptions. I hope readers of this blog will look into the history of this debate with an open mind, not the closed groupthink that plagues some (but not all) neoclassical institutions regarding capital theory. I thank all of you who have read this post, and sorry for the radio silence on this app!

Have you read Stiglitz's paper on CCC (https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/260245?journalCode=jpe) and Farhi's work on theory of capital (https://www.nber.org/papers/w25293) ?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QRFRuj0myTI